Table of Contents

As already mentioned, after the reforms of Shang Yang, the Qin kingdom became a powerful power. Since that time, the Qin rulers have been on the path of aggression. Using the internal contradictions of the ancient Chinese kingdoms and their feuds, the Qin Wangs seized one territory after another and, after a fierce struggle, subjugated all the states of Ancient China. In 221 BC, Qin conquered the last independent Qi kingdom in the Shandong Peninsula. Qin Wang assumed the new title of “huangdi” – emperor – and went down in history as Qin Shi Huang – “The First Emperor of Qin”. The capital of the Qin Kingdom, Xianyang, was declared the capital of the empire.

Qin Shi Huang did not limit himself to conquering the ancient Chinese kingdoms, but continued to expand northward, where the Xiongnu tribal alliance was being formed. The 300,000-strong Qin army defeated the Xiongnu and pushed them back behind the Yellow River Bend. To secure the northern border of the empire, Qin Shi Huang ordered the construction of a giant fortification — the Great Wall of China. He made conquests in Southern China and Northern Vietnam. At the cost of huge losses, his armies managed to achieve the nominal subordination of the ancient Vietnamese states of Namviet and Aulak.

Qin Shi Huang spread the Shang Yang rule throughout the country, creating a military-bureaucratic empire led by a single-power despot. The Qin people occupied a privileged position in it, they owned all the leading official positions. Hieroglyphic writing was unified and simplified. The law established the common civil name “blackheads”for all full-fledged freemen. Qin Shi Huang’s activities were conducted with drastic measures.

Terror reigned in the country. All those who expressed dissatisfaction were executed, and under the law of mutual bail, accomplices were enslaved. Due to the enslavement of the masses of prisoners of war and convicted by the courts, the number of state slaves turned out to be huge.

“The Qin established markets for slaves and female slaves in corrals along with cattle; managing their subjects, they completely controlled their lives,” ancient Chinese authors report, seeing this as almost the main reason for the rapid fall of the Qin dynasty. Far — flung campaigns, the construction of the Great Wall, irrigation canals, roads, extensive urban planning, the construction of palaces and temples, the creation of a tomb for Qin Shi Huang-recent excavations have revealed the vast scale of this underground mausoleum-required enormous costs and human sacrifices. The heaviest labor duties fell on the shoulders of the bulk of the working population.

In 210 BC, at the age of 48, Qin Shi Huang died suddenly, immediately after his death, a powerful uprising broke out in the empire. The most successful of the rebel leaders, a native of the rank-and-file communists, Liu Bang rallied the forces of the popular movement and attracted to his side the experienced military enemies of Qin from the hereditary aristocracy. In 202 BC, Liu Bang was proclaimed emperor and became the founder of the new Han Dynasty.

Archer of the Imperial Guard. Terracotta. Late 3rd century BC From the excavation of Qin Shi Huang’s grave near Xi’an.

China’s first ancient empire, the Qin, lasted only a decade and a half, but it laid a solid socio-economic foundation for the Han Empire. The new empire became one of the strongest powers of the ancient world. Its more than four centuries of existence was an important stage in the development of the whole of East Asia, which, as part of a world-historical process, covered the era of the rise and collapse of the slave-owning mode of production. For the national history of China, this was an important stage in the consolidation of the ancient Chinese people. To this day, the Chinese call themselves Han, an ethnic self-designation that originates from the Han Empire.

The history of the Han Empire is divided into two periods:

Having come to power on the crest of the anti-Qin movement, Liu Bang abolished the laws of Qin, eased the burden of taxes and duties. However, the Qin administrative division and bureaucratic system of government, as well as most of the economic institutions of the Qin Empire, remained in force. True, the political situation forced Liu Bang to violate the principle of unconditional centralization and distribute part of the land in the possession of his associates — the seven strongest of them received the title “wang”, which now became the highest aristocratic rank. The fight against their separatism was the primary domestic political task of Liu Bang’s successors. Finally, the power of the Vans was broken under the Emperor Udi (140-87 BC).

In the agricultural production of the empire, the bulk of the producers were free farmers-community members. They were subject to land taxes (from 1/15 to 1/zo of the crop), poll taxes, and household taxes. Men carried out work (for a month a year for 3 years) and military (2-year army and annually 3-day garrison) duties. Farmers made up a certain part of the population in the cities as well. The capital of the empire, Chang’an (near Xi’an) and the largest cities, such as Linzi, numbered up to half a million, many others — more than 50 thousand inhabitants. In the cities, self-government bodies functioned, which were a characteristic feature of the ancient Chinese “urban culture”.

Slavery was the basis of production in industry, both private and public. Slave labor, although to a lesser extent, was widely used in agriculture. The slave trade at this time is rapidly developing. Slaves could be bought in almost every city, and in the markets they were counted like working cattle, on the “fingers of their hands”. Shipments of chained slaves were transported hundreds of kilometers away.

By the time of Wudi’s rule, the Han state had developed into a strong centralized state. The expansion that unfolded under this emperor was aimed at seizing foreign territories, subjugating neighboring peoples, dominating international trade routes, and expanding foreign markets. From the very beginning, the empire was threatened by the invasion of the Xiongnu nomads. Their raids on China were accompanied by the theft of thousands of prisoners and even reached the capital. Udi set a course for a decisive fight against the Xiongnu. The Han armies managed to push them back from the Great Wall, and then expand the territory of the empire in the northwest and establish the influence of the Han Empire in the Western Region (as Chinese sources called the Tarim River basin), through which the Great Silk Road passed. At the same time, Udi waged wars of conquest against the Vietese states in the south and in 111 BC forced them to submit, annexing the lands of Guangdong and the north of Vietnam to the empire. After that, Han naval and land forces attacked the ancient Korean state of Joseon and forced it to recognize the Han power in 108 BC.

The embassy of Zhang Qian (died 114 BC), sent to the west under Wudi, opened up a vast world of foreign culture to China. Zhang Qian visited Dasha (Bactria), Kangyu, Davan (Ferghana), found out about Anxi (Parthia), Shendu (India) and other countries. Ambassadors from the Son of Heaven were sent to these countries. The Han Empire established ties with many states on the Great Silk Road — an international transcontinental highway that stretches for a distance of 7 thousand km from Chang’an to the Mediterranean countries. Along this route, the caravans were drawn in a continuous line, according to the figurative expression of the historian Sima Qian (145-86 BC), “one did not let the other out of sight.”

From the Han Empire to the West, iron, considered the best in the world, nickel, precious metals, lacquer, bronze, and other art and craft products were transported. But the main export item was silk, which was then produced only in China. International, trade and diplomatic ties along the Great Silk Road promoted the exchange of cultural achievements. Of particular importance to Han China were the agricultural crops borrowed from Central Asia: grapes, beans, alfalfa, pomegranate and nut trees. However, the arrival of foreign ambassadors was perceived by the Son of Heaven as an expression of submission to the Han Empire, and the goods brought to Chang’an as a “tribute” to foreign “barbarians”.

Udi’s aggressive foreign policy required enormous resources. Taxes and duties have greatly increased. Sima Qian notes: “The country is tired of continuous wars, the people are sad, the supplies are depleted.” Already at the end of the reign of Udi, popular unrest broke out in the empire.

In the last quarter of the first century BC, a wave of slave revolts swept through the country. The most far-sighted representatives of the ruling class were aware of the need for reforms to reduce class contradictions. Indicative in this respect is the policy of Wang Mang (9-23 AD), who carried out a palace coup, overthrew the Han Dynasty and declared himself emperor of the New Dynasty.

The decrees of Wang Mang prohibited the purchase and sale of land and slaves, and it was supposed to endow the poor with land by withdrawing its surplus from the rich of the community. However, after three years, Wang Mang was forced to cancel these regulations due to the resistance of the owners. Wang Mang’s laws on the smelting of coins and the rationing of market prices, which represent an attempt to interfere with the state’s economy, also failed. The mentioned reforms not only did not mitigate social contradictions, but also led to their further aggravation. Spontaneous uprisings swept across the country. The “Red Eyebrows” movement, which began in 18 A.D. in Shandong, where the population’s distress was multiplied by the disastrous Yellow River flood, had a special scope. Chang’an fell into the hands of the rebels. Wang Mang was beheaded.

The spontaneous protest of the masses, their lack of military and political experience, led to the fact that the movement was led by representatives of the ruling class, who were interested in overthrowing Wang Mang and putting their protege on the throne. He became the scion of the Han house, known as Guang Wudi (25-57 AD), who founded the Younger Han Dynasty. Guan Wudi began his reign with a punitive campaign against the “Red Eyebrows”. By 29, he was able to break them, and then suppress the other centers of the movement.

The scale of the uprisings showed the need for concessions to the lower classes. If earlier any attempts from above to restrict private slavery and invade the rights of landowners were resisted by the rich, now in the face of the real threat of mass insurrection, they did not protest against the laws of Guang Wudi, which prohibited the branding of slaves, limited the right of the owner to kill slaves, and a number of measures aimed at reducing slavery and some relief for the people.

In 40 AD, a people’s liberation uprising broke out against the Han authorities in North Vietnam under the leadership of the Chung sisters, which Guan Udi managed to suppress with great difficulty only by 44 AD. In the second half of the first century, having skillfully used (and to a certain extent provoked) the split of the Xiongnu into northern and southern, the empire began to restore Han rule in the Western Region, which under Wang Mang fell under the rule of the Xiongnu. By the end of the first century, the Han Empire managed to establish influence in the Western Region and establish hegemony on this segment of the Silk Road.

The Han governor of the Western Region, Ban Chao, launched an active diplomatic activity at this time, aiming to achieve direct contacts with Daqin (Great Qin, as the Han called the Roman Empire). However, the embassy he sent only reached Roman Syria, being detained by Parthian merchants.

Since the second half of the first century AD, intermediary Han-Roman trade has been developing. The ancient Chinese first saw the Romans in 120 AD, when a troupe of traveling magicians from Rome arrived in Luoyang and performed at the court of the Son of Heaven. At the same time, the Han Empire established links with Hindustan via Upper Burma and Assam, and established a sea connection from the port of Bakbo in Northern Vietnam to the east coast of India, and through Korea to Japan.

On the southern sea route in 166, the first “embassy” from Rome, as a private Roman trading company called itself, arrived in Luoyang. Since the middle of the second century, with the loss of the empire’s hegemony on the Silk Road, the Han people’s foreign trade with the countries of the South Seas, Lanka and Hanchipura (South India) has been developing. The Han Empire is desperately and in all directions rushing to foreign markets. It seemed that the Han power had never reached such power. It was home to about 60 million people, which was more than 1/5 of the world’s population at that time.

However, the apparent prosperity of the Late Han Empire was fraught with deep contradictions. By this time, there were serious changes in its social and political structure. Slave farms continued to exist, but the estates of the so-called strong houses became more and more widespread, where often, along with slaves, the labor of “those who do not have their own land, but take it from the rich and cultivate it”was widely used. This category of workers found themselves in personal dependence on the land owners. Under the protection of strong houses, there were several thousand such families.

The area of arable land registered by the state steadily decreased, the number of taxable population fell catastrophically: from 49.5 million people in the middle of the second century to 7.5 million according to the census of the middle of the third century. The estates of strong houses became economically closed farms.

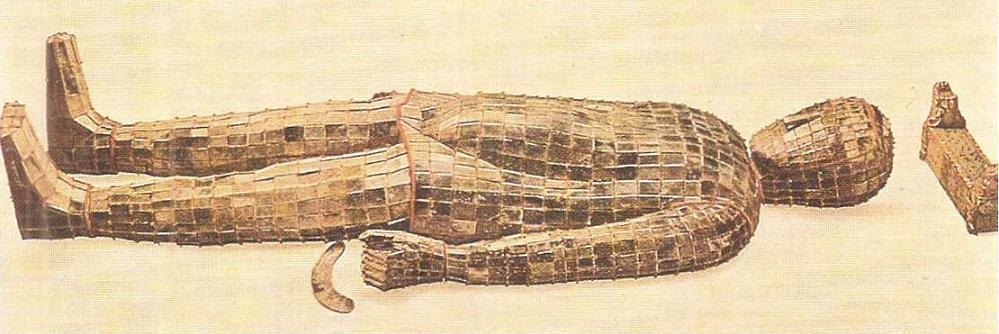

Funeral vestment of the wife of the brother of the emperor Udi from 2156 jade plates, fastened with gold threads. Henan. II century BC.

The rapid decline of commodity-money relations began. The number of cities in comparison with the border of our era has been reduced by more than half. At the very beginning of the third century, a decree was issued on the replacement of monetary payments in kind in the empire, and then the coin was officially abolished and silk and grain were introduced into circulation as commodity money. Since the second quarter of the second century, chronicles almost annually note local uprisings — for half a century, more than a hundred of them have been recorded.

In the context of the political and deep socio-economic crisis in the empire, the most powerful uprising in the history of Ancient China, known as the “Yellow Bandages”uprising, broke out. It was led by the healing magician Zhang Jiao, the founder of a secret pro-Daoist sect that had been plotting an uprising for 10 years. Zhang Jiao created a 300,000-strong paramilitary organization. According to the reports of the authorities, “the entire empire adopted the faith of Zhang Jiao.”

The movement broke out in 184 in all parts of the empire at once. The rebels wore yellow headbands as a sign of the victory of the just Yellow Sky over the Blue Sky-the unrighteous Han Dynasty. They destroyed government buildings, killed government officials. The revolt of the “Yellow Bandages” had the character of a broad social movement with an unmistakable eschatological connotation. Speaking under the religious guise of the teaching of the Way of the Great Welfare (Taipingdao), the Yellow Armbands movement was the first in the history of China to revolt the oppressed masses with their own ideology. The authorities were powerless to cope with the uprising, and then the armies of strong houses rose to fight the “Yellow Armbands” and together they brutally dealt with the rebels. In commemoration of the victory, a tower of hundreds of thousands of severed heads of the “yellows”was built at the main gate of the capital. The division of power between the executioners of the movement began. Their feuds ended with the collapse of the Han Empire: in 220 BC. it was divided into three kingdoms, in which the process of feudalization was actively going on.

The Han period was a kind of culmination of the cultural achievements of Ancient China. On the basis of centuries-old astronomical observations, the lunar-solar calendar was improved. In 28 BC, Han astronomers first noted the existence of sunspots. An achievement of world significance in the field of physical knowledge was the invention of the compass in the form of a square iron plate with a magnetic “spoon” freely rotating on its surface, the handle of which invariably pointed to the south.

The scientist Zhang Heng (78-139) was the first in the world to construct a prototype of a seismograph, build a celestial globe, and describe 2,500 stars, including them in 320 constellations. He developed a theory of the Earth and the boundlessness of the Universe in time and space. Han mathematicians knew decimals, invented negative numbers for the first time in history, and refined the value of the number pi. The medical catalog of the first century lists 35 treatises on various diseases. Zhang Zhongjing (150-219) developed methods for pulse diagnosis and treatment of epidemiological diseases.

The end of the ancient era was marked by the invention of mechanical engines that use the force of falling water, a water-lifting pump, and the improvement of the plow. Han agronomists create works describing the bed culture, the system of variable fields and alternating crops, methods of fertilizing the land and pre-sowing impregnation of seeds, they contain guidelines for irrigation and reclamation. The treatises of Fan Shenzhi (I century) and Cui Shi (II century) summarized the centuries-old achievements of the ancient Chinese in the field of agriculture.

Among the outstanding achievements of material culture is the ancient Chinese lacquer production. Lacquerware was an important item in the foreign trade of the Han Empire. Weapons and items of military equipment were covered with varnish to protect wood and fabrics from moisture, and metal from corrosion. They decorated architectural details, items of funeral equipment, varnish was widely used in fresco painting. Chinese lacquers were highly valued for their unique physical and chemical properties, such as the ability to preserve wood, resist the effects of acids and high temperatures (up to 500°C).

Since the “opening” of the Great Silk Road, the Han Empire has become a world-famous supplier of silk. China was the only country in the ancient world that mastered the silkworm culture. In the Han Empire, silkworm farming was a domestic occupation of farmers. There were large private and state-owned silk mills (some numbered up to a thousand slaves). The export of silkworms outside the country was punishable by death. But such attempts were still made. Zhang Qian, during his embassy mission, learned about the export of silkworms from Sichuan to India in the cache of a bamboo staff by foreign merchants. And yet no one managed to find out the secrets of sericulture from the ancient Chinese. Fantastic assumptions were made about its origin: in Virgil and Strabo, for example, it was said that silk grows on trees and is “brushed off” from them.

Ancient sources mention silk from the first century BC. e. Pliny wrote about silk as one of the most valued luxury items by the Romans, because of which huge sums of money were pumped out of the Roman Empire every year. The Parthians controlled the Han-Roman silk trade, charging at least 25% of its selling price for mediation. Silk, which was often used as money, played an important role in the development of international trade relations between the ancient peoples of Europe and Asia. India was also an intermediary in the silk trade. Ties between China and India predate the Han era, but at this time they are particularly lively.

The great contribution of Ancient China to the universal culture was the invention of paper. Its production from the waste of silk cocoons began before our era. Silk paper was very expensive, available only to a select few. The real discovery, which had a revolutionary significance for the development of human culture, was paper when it became a cheap mass-produced material for writing. The invention of a publicly available method of producing paper from wood fiber is traditionally associated with the name of Cai Lun, a former slave originally from Henan, who lived in the II century., however, archaeologists date the oldest samples of paper to the II-I centuries BC.

The invention of paper and ink created the conditions for the development of the technique of prints, and then the emergence of the printed book. The improvement of Chinese writing was also associated with paper and ink: in the Han period, the standard style of writing Kaishu was created, which laid the foundation for modern hieroglyphics. Han materials and means of writing were, along with hieroglyphics, adopted by the ancient peoples of Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, which in turn influenced the cultural development of Ancient China — in the field of agriculture, in particular rice farming, navigation, and artistic crafts.

Lacquer utensils with inscriptions:”Sir, taste the dish”, “Sir, taste the wine”. Hunan. Mid-II century BC.

During the Han period, ancient monuments are collected, systematized, and commented on. In fact, all that remains of the ancient Chinese spiritual heritage has come down to us thanks to the records made at this time. At the same time, philology and poetics were born, and the first dictionaries were compiled. There were major works of fiction, primarily historical. The brush of the” father of Chinese history “Sima Qian belongs to the fundamental work “Historical Notes” (“Shiji”) — a 130-volume history of China from the mythical first ancestor of Huangdi to the end of the reign of Wudi.

Sima Qian sought not only to reflect the events of the past and present, but also to comprehend them, to trace their internal regularity, ” to penetrate into the essence of change.” Sima Qian’s work sums up the previous development of ancient Chinese historiography. At the same time, he departs from the traditional style of weather chronicling and creates a new type of historical composition. “Shiji” is the only source on the ancient history of the neighboring peoples of China. An outstanding stylist, Sima Qian vividly and succinctly gave descriptions of the political and economic situation, life and mores. He created a literary portrait for the first time in China, which puts him on a par with the largest representatives of Han literature. The Historical Notes became a model for subsequent ancient and medieval historiography in China and other countries of the Far East.

Sima Qian’s method was developed in the official “History of the Elder Han Dynasty” (“Han Shu”). The main author of this work is considered to be Ban Gu (32-93). “The History of the Elder Han Dynasty” is designed in the spirit of orthodox Confucianism, the presentation strictly adheres to the official point of view, often diverging in the assessment of the same events with Sima Qian, whom Ban Gu criticizes for his commitment to Taoism. “Han Shu” opened a series of dynastic stories. Since then, according to tradition, each of the dynasties that came to power has compiled a description of the reign of its predecessor.

As the most brilliant poet among the galaxy of Han writers, Sima Xiangzhu (179-118) stands out, praising the power of the empire and the “great man” himself — the autocrat of Udi. His work continued the tradition of the Chu ode, which is characteristic of Han literature, which absorbed the song and poetic heritage of the peoples of Southern China. The ode “Beauty” continues the poetic genre started by Sun Yu in “Ode to the Immortal”. Among the works of Sima Xiangzhu, there are imitations of folk lyrical songs, such as the song “Fishing Rod”.

The system of imperial government included the organization of national cults as opposed to the aristocratic local ones. This task was pursued by the Music Chamber created under the Udi (Yuefu), where folk songs were collected and processed, including “songs of distant barbarians”, and ritual chants were created. Despite its utilitarian nature, the Music Chamber has played an important role in the history of Chinese poetry. Thanks to it, the works of folk song art of the ancient era have been preserved.

The author’s songs in the style of yuefu are close to folklore, for them the subject of imitation was folk songs of different genres, including labor and love. Among the love lyrics, the works of two poetesses stand out — “Weeping for a Gray Head” by Zhuo Wenjun (II century BC), where she reproaches her husband, the poet Sima Xiangzhu, for infidelity, and” Song of My Resentment ” by Ban Jieyu (I century BC), in which the image of an abandoned snow-white fan represents the bitter fate of an abandoned lover. Yuefu’s lyrics reached a special rise in the Jianan period (196-220), which is considered the golden age of Chinese poetry. The best of the literary yuefu of this time were created on the basis of folk works.

Only in the rarest cases were songs preserved that expressed the rebellious spirit of the people. Among them are “The Eastern Gate”, “East of the Pingling Mound”, as well as quatrains-ditties of the Yao genre, in which social protest sounds up to the call to overthrow the emperor (especially in the so-called tongyao, obviously slave songs). One of them, attributed to the leader of the” Yellow Bandages “Zhang Jiao, begins with the proclamation:” May the Blue Sky perish!”, in other words, the Han Dynasty.

A fragment of a funeral silk banner depicting the consort of the Jingdi Emperor. Hunan. Mid-II century BC.

By the end of the Han Empire, the content of secular poems increasingly becomes anacreontic and fairy-tale themes. Mystical and fantastic literature is distributed. The authorities encourage theatrical rites and secular performances. The organization of spectacles becomes an important function of the state. However, the beginnings of stage art did not lead to the development of drama as a kind of literature in ancient China.

In the Qin-Han era, the main features of traditional Chinese architecture developed. Judging by the fragments of frescoes from Han burials, the rudiments of portraiture appear in this period. The discovery of the Qin monumental sculpture was a sensation. Recent excavations of Qin Shi Huang’s grave have revealed an entire “clay army” of the emperor, consisting of three thousand foot soldiers and horsemen, made in full size. This discovery suggests the appearance of portrait sculpture in the early Imperial period.

Since the time of Udi, the official ideology of the Han Empire has been transformed into Confucianism, which has become a kind of state religion. In Confucianism, the ideas of the conscious intervention of Heaven in the lives of people are strengthened. The founder of Confucian theology, Dong Zhongshu (180-115), developed the theory of the divine origin of imperial power, and proclaimed Heaven as the supreme, almost anthropomorphic deity. He initiated the deification of Confucius. Dong Zhongshu demanded the “eradication of all the hundred schools” except the Confucian one.

The religious-idealistic essence of Han Confucianism is reflected in the creed of Liu Xiang (79-8 BC), who claimed that ” the spirit is the root of heaven and earth and the beginning of all things.” Under the influence of the social and ideological processes taking place in the empire, Confucianism at the turn of our era split into two main trends:

The state is increasingly taking advantage of Confucianism, intervening in the struggle of its various interpretations. The Emperor initiates religious and philosophical disputes, seeking to end the schism of Confucianism. The Council of the end of the first century AD formally put an end to the differences in Confucianism, recognized all apocryphal literature as false, and approved the doctrine of the school of New Texts as the official religious orthodoxy. In 195 AD, the state copy of the Confucian “Pentateuch” in the version of the School of New Texts was carved on the stone. Since that time, the violation of the Confucian precepts, incorporated into the criminal law, was punishable up to the death penalty as the “most serious crime”.

With the beginning of the persecution of “false” teachings, secret sects of a religious and mystical nature began to spread in the country. Those who disagreed with the ruling regime were united by a religious Taoism opposed to Confucianism, which dissociated itself from philosophical Taoism, which continued to develop ancient materialistic ideas.

At the beginning of the second century, the Taoist religion took shape. Its founder is considered to be Zhang Daolin from Sichuan, who was called a Teacher. His prophecies about achieving immortality attracted crowds of the destitute, who lived in a closed colony under his command, laying the foundation for secret Taoist organizations. By preaching the equality of all on the basis of faith and condemning wealth, the Taoist “heresy” attracted the masses. At the turn of the second and third centuries, the movement of religious Taoism, led by the Five Measures of Rice sect, led to the creation of a short-lived theocratic state in Sichuan.

The tendency to transform ancient philosophical teachings into religious doctrines, manifested in the transformation of Confucianism and Taoism, was a sign of deep socio-psychological changes. However, not the ethical religions of Ancient China, but Buddhism, having penetrated into China at the turn of our era, became for the agonized Late Han world the world religion that played the role of an active ideological factor in the process of feudalization of China and the entire East Asian region.

Achievements in the field of natural and humanitarian knowledge created the basis for the rise of materialistic thought, which was manifested in the work of the most outstanding Han thinker Wang Chong (27-97). In an atmosphere of ideological pressure, Wang Chong had the courage to challenge Confucian dogmas and religious mysticism.

In his treatise “Critical Reasoning” (“Lunheng”), a coherent system of materialistic philosophy is set out. Wang Chong was a scholarly critic of Confucian theology. The philosopher contrasted the deification of heaven with the materialistic and atheistic statement that “heaven is a body like the earth”. Wang Chong supported his statements with clear examples that “everyone can understand”. “Some people believe,” he wrote, ” that the sky gives birth to five grains and produces mulberries and hemp just to feed and clothe people. It means to liken the sky to a slave or slave, whose purpose is to cultivate the land and feed silkworms for the benefit of people. Such a judgment is false, it contradicts the naturalness of things themselves.”

Wang Chong proclaimed the unity, eternity, and materiality of the world. Continuing the traditions of ancient Chinese natural philosophy, he recognized the source of existence as the subtlest material substance of qi. Everything in nature arises naturally, as a result of the condensation of this substance, regardless of any supramundane force. Wang Chong denied the innate knowledge, the mystical intuition that Confucians gave to the ancient sages, and saw the way of knowledge in the sensory perception of the real world. “Among the beings born of heaven and earth, man is the most valuable, and this value is determined by his ability to know,” he wrote. Wang Chong developed the idea of the dialectical unity of life and death: “Everything that has a beginning must have an end. Everything that has an end must have a beginning… Death is the result of birth, and in birth lies the inevitability of death.”

He opposed the Confucian concept of the cultural exclusivity of the ancient Chinese, their moral superiority over the supposedly ethically inferior “barbarians”.

In many concrete examples, Wang Chong argued that customs, mores, and human qualities are not determined by immutable innate properties. In this, he agreed with other Han thinkers who denied the fundamental differences between the “barbarians” and the ancient Chinese. Wang Chong was one of the most educated people of his time. He set wide educational tasks, exposing from a rationalistic position the prejudices and superstitions common among the people.

Wang Chong’s materialistic worldview, especially his teaching about “naturalness” (zizhan) — the naturally necessary process of developing the objective world, played an important role in the history of Chinese philosophy. But in his contemporary reality, Wang Chong’s philosophy could not be recognized.

His creation was even persecuted for criticizing Confucius. Only a millennium later, his manuscript was accidentally discovered, giving the world the legacy of one of the most outstanding materialists and enlighteners of ancient times.

The Zhanguo-Qin-Han epoch had, in principle, the same significance for the historical development of China and all of East Asia as the Greco-Roman world had for Europe. Ancient Chinese civilization laid the foundations of a cultural tradition that can be traced further throughout the centuries-old history of China up to Modern and modern times.

Tell your friends:

Rating: